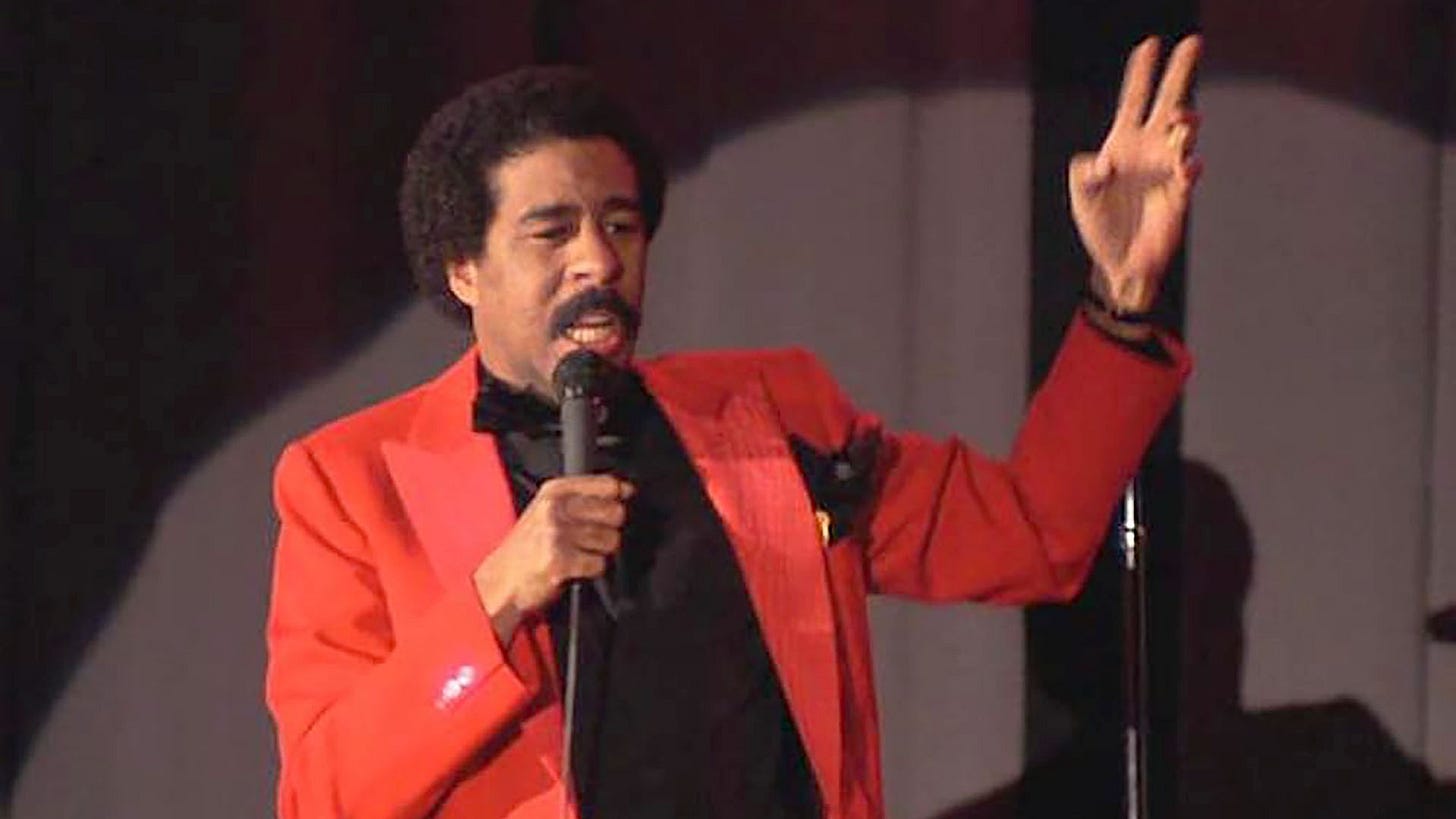

Richard Pryor had a routine about his first trip to Africa, where everybody looked like someone he knew, including a president who resembled the boxer Joe Frazier and a diplomat who took after an old wino from his neighborhood. Pryor’s visit gave him a new perspective on the consequences of Black Africans’ removal to America, which he summed up this way: “Old wino, you were supposed to be a diplomat!”

I thought of Pryor’s bit when I went to Russia for the first time, in 1994, and met with executives of newly privatized companies. I had encountered business leaders in my prior job as an American M&A lawyer — mostly silver-haired (or silver-toupéed) men who looked fine, but never like my father or anyone else in my family. In Russia, though, they all reminded me of Chaim Sawikin and his circle of Eastern European immigrant friends.

I was amazed, for example, when I arrived at Gorkovsky Avtomobilny Zavod (GAZ) in Nizhny Novgorod and found a CEO who – with his red Slavic face, thick neck, and bald head – evoked my dad’s childhood friend “Meshuggeneh” Moishe Sempf. Then there was the CFO of a Moscow telecom, a middle-aged woman with a hair-helmet dyed red – dressed incongruously for our business meeting in a t-shirt with “Sexy” in sequins across the chest – who was the doppelganger of Raisa Karpenkop of Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn.

Moishe’s manic energy and impulsivity, which had gained him the nickname “meshuggeneh,” they would today quickly diagnose as ADHD and move on. Yet it was this energy, his relentless wheeling and dealing – trading underwear for bread, bread for boots, boots for travel documents – that helped explain how he and my father together had survived wartime Russia as teenaged refugees.1

Moishe arrived in America penniless but ultimately made his way chauffeuring a limo he owned, despite never really learning English and speaking in a near-incomprehensible Yiddish accent that he told unsuspecting tourist passengers was French or Swedish.

GAZ, GUM, RED OCTOBER

At GAZ, I accompanied the Moishe lookalike CEO to his office, which was full of Soviet-era memorabilia, including a flag decorated with the hammer-and-sickle. A holdover Red Director who’d survived privatization, he now had the task of generating actual profits from selling the “Volga,” a boxy fume-belching sedan once issued to Communist Party nomenklatura. His tens of thousands of employees, many of whom had observed the principle “We Pretend to Work and They Pretend to Pay Us,” were undergoing a (literally) sobering transition.

All I remember of my discussion with the CEO via his translator is a few confidently stated but hardly relevant proclamations amid flashes of gold teeth. At some point it became clear to me that he neither understood how to generate profits nor intended to learn, and that my fund’s GAZ stake would never be worth anything. But at least he was friendly. When my late partner Brom went to Siberia to see our investee oil company Surgutneftegaz, the management angrily disputed that we were even shareholders. Brom insisted that we were and kept at it until they invited him to leave town.

As I exited GAZ, the jovial Red Director handed me a model Volga to take home. My partners and I came to understand that a company’s gift of a toy meant there would be no dividends or other returns. Although we made a few bad early investments, we did accumulate a shelf of model cars, airplanes, and oil rigs. (A pack of stray dogs wandering the factory grounds was often an equally accurate indicator that no shareholder returns were coming soon.)

A no less strange encounter was with the CEO of GUM Department Store, the magnificent 19th century building that runs along the side of Red Square. Like the GAZ guy, he was a holdover from the Soviet era and had what I’d call a complex attitude toward shareholders. He seemed to believe that we were entitled to some returns, as long as we didn’t get pushy about it. We were therefore like his store workers, who were allowed to steal a little. The CEO explained that by tolerating theft as part of employee comp, GUM avoided the social contributions attached to wages. He seemed to want me to congratulate him for his Western biznezman-type thinking.

Another 1994 Firebird Fund purchase, Krasny Oktyabr (Red October), made the waxy chocolates Soviets had enjoyed for almost a century. Along with GUM, Red October was a prominent early Russian privatization – it was a Red October share that Yeltsin had gifted then-Treasury Secretary Lloyd Bentsen when he visited the Moscow Stock Exchange.2 We were already stockholders when I arrived at the Red October factory, in a spectacular setting above the Moskva River.

At the traditional T-shaped Soviet-era conference table, I was given chai and an assortment of chocolates, which were tasty despite their waxiness. The CEO explained that his strategy was to target the high-end candy consumer. When I asked how Red October had done in 1993, he said that they’d produced 100,000 tons of chocolate. For 1994, the plan was 110,000 tons. It struck me then that to compete with Godiva et al., it would be necessary to approach chocolate more like a luxury item than like pig iron, but I didn’t want to say so and hurt his feelings. Also, he reminded me of my father’s friend Julian Rosenbaum.3

STOLEN FUTURES

Like the American Blacks in the Richard Pryor routine, my father and his friends had their potential futures stolen from them. My father was an intelligent man, a beautiful writer in his native Yiddish, who’d had to leave school at 15 and then self-educated throughout his life. He got along as a printer in America, even published a regular column in the Yiddish Forward, but I picture him, in an alternate Hitler-less world, as a beloved teacher in a vibrant Warsaw Jewish community.

As for Moishe, he did fine in New York with his limo and his side hustles. But, in this alternate world where he’d stayed in Poland and – as long as I’m dreaming – where Jews had equal rights to Christians, the drive and resourcefulness that let him survive the war might have been channeled into something more ambitious.

“Meshuggeneh Moishe, you were supposed to be a CEO!”

These amazing experiences are detailed in my father’s memoir of World War II, To Paradise and Back (suitable for younger readers). I will make it free for the five days following this posting. https://www.amazon.com/Paradise-Back-Charles-Sawikin-ebook/dp/B07FSDNKN6/ref=sr_1_1?crid=3QWD2NQ4NOWG7&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.j4vgITYG0dx7bYrrnfx3pOHzl8PVfTeSvEVHpE2kLlM.BLGSj9VBH5MqqQziqISTPyGFDz97NtW8UddS_UgoOVY&dib_tag=se&keywords=to+paradise+and+back+sawikin&qid=1743372004&sprefix=sawikin+to+paradis%2Caps%2C101&sr=8-1

Too bad for Bentsen. If he’d gotten Lukoil instead of Red October, it would’ve been worth something.

We held onto Red October despite this lack of sophistication, figuring they’d eventually move the factory to the suburbs and sell the land for a bundle. This did happen (the old site is now an arts complex), but shareholders didn’t benefit. In frontier markets, when a company’s value is mainly in the underlying real estate, it tends to disappear from the balance sheet.