In the 1980’s, in my twenties and with a family history of heart disease, I began thinking about reducing risk through diet. One of America’s leading nutrition experts was New York Times writer Jane Brody, who had published books advocating a low-fat, high carbohydrate diet.1 This was consensus at the time, but if I’d continued to follow her plan — and hadn’t been diagnosed as diabetic along the way — I might not be alive today.

While Brody herself changed her opinions, the high carb low-fat ideology dominated U.S. nutrition for 20 years until the 00s, when the protein-heavy Atkins Diet became the craze. Atkins was soon debunked and supplanted by Keto, Mediterranean, South Beach, and others. By now, there is plenty of nutrition science to guide us, yet I still hear enough wrong assumptions to fear that the current twentysomethings will be no healthier than we were.

The Rise of the Carb Monster2

The low-fat ideology of the 1980s dates to the 1940s, when a correlation was first found between a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet and heart disease. At the time, not all scientists agreed, nor did all studies bear out the link, and the low-fat diet was mainly prescribed for people with heart disease. Anyway, most Americans stuck with their fatty diets, even after another study in 1957 by the American Heart Association (AHA) made the same fat-cardiovascular connection.

In the 1960s, the AHA continued to cite fat intake as a risk factor for heart disease, although it still only recommended substituting part of the American diet with lower-fat foods. I remember as a boy my mother yelling at my high-cholesterol father to eat less of the cheese he loved and to spread margarine instead of butter on his toast. (“Look at him, he puts cheese on cheese!” she’d stage whisper to me, enlisting my support in her war on fat.)

While fat reduction was a goal of some nutritionally informed people like my mother, it only became a national priority after the 1977 publication of “Dietary Goals in the United States,” a report by a Senate committee under George McGovern. This called for reduced consumption of high-fat foods, sugar, and salt, and more consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, poultry, and fish, and nonfat instead of whole milk.

The Senate report led to publication of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, which promoted a low-fat diet. The Surgeon General, American Cancer Society and American Medical Association joined the low-fat chorus – even though there still had never been a definitive study proving the relationship between fat, cholesterol, and heart disease.3

The food industry at first resisted but soon realized that it could profit by substituting sugar for fat – by this point the anti-sugar part of the 1977 report had been pushed to the side. This led to the “SnackWell’s Phenomenon,” when the supermarkets abounded with low-fat, high-calorie industrial foods presented as healthy. The recommendation to consume whole grains transformed into bread and cereals of any kind. In 1988, the AHA began issuing (for a fee) a “heart healthy” seal of approval with a checkmark. The seal appeared on foods like Frosted Flakes and Low-Fat Pop Tarts.

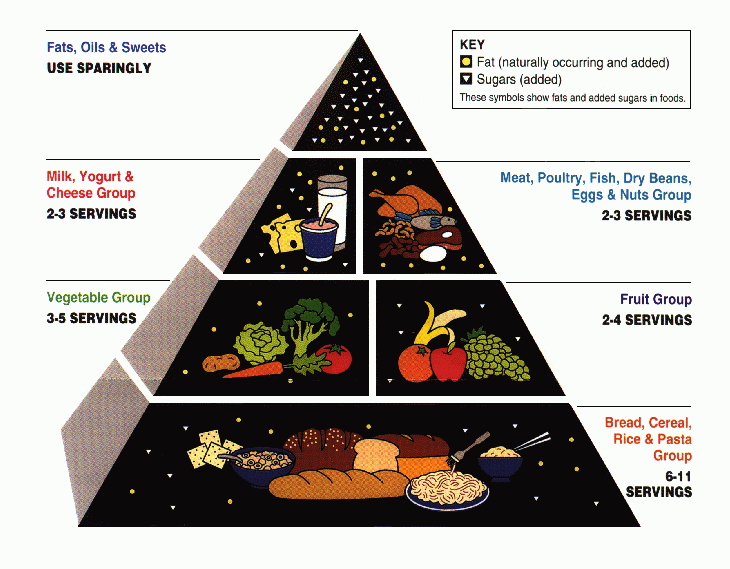

In 1992, the USDA released its first Food Pyramid, its base being the “Bread, Cereal, Rice & Pasta Group,” at 6-11 servings, with no distinction made as to the kind of grains. A parent could assume that the dietary authorities suggested Wonder Bread was a great choice for kids. Meat, milk, eggs, fish, nuts, and cheese were all near the top of the pyramid with 2-3 servings.

The Lethal Experts

Nutrition mavens such as Prevention Magazine and Jane Brody went all-in on the low-fat, high carb diet. With the government and every major medical organization in agreement, why deviate? Pro low-fat books like Brody’s proliferated — my mother had one by an extreme low-fat advocate, Dr. Dean Ornish (my father called him Gornisht — nothing in Yiddish — in reference to his program).

My wife cooked dinners often consisting of pasta with no meat or cheese, of which I had to consume seconds and thirds to feel full. For dessert I might enjoy a few SnackWell’s. My breakfasts were cold cereal or a muffin, and lunches usually lettuce and tomato on “wheat bread” (not necessarily whole grain). We’d order Chinese food, which per Brody should be fine if you got chicken or vegetables. What I didn’t consider, or even know about, was the million grams of sugar in the sauces.

On this diet I got neither fat nor thin, but what I did get was Type 2 diabetes, soon after turning 40. Being genetically prone, I’d eventually have gotten it anyway, and the early onset turned out to be a lucky break. I went on medication mitigating a diet that for years after my diagnosis continued to be exactly wrong for me. I’m pretty sure Metformin saved me from a heart attack.

In defense of Jane Brody, by the early 1990s she was questioning a one-size-fits-all low-fat diet and by decade’s end had switched to the Mediterranean Diet. By then, evidence indicated that low-fat, high carb was only making Americans fatter. New studies explained why, including one at Rockefeller University showing that a diet consisting below 20% of fat causes the body to produce saturated fat from carbohydrates, a substitution that raises triglycerides while lowering high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) (“good” cholesterol).

Another study showed that margarine, while it was promoted as healthy in the 70s, contained trans-fats that lowered HDLs and raised LDLs (“bad” cholesterol). My father would’ve been far better off with the butter he craved than Parkay; in fact, the dear schlimazel would’ve been better off generally if he’d just eaten what he felt like and gone on a statin, as basically all male cardiologists over 40 years old do.

A Times science reporter, Gina Kolata, began in the 1990s to examine the assumptions behind low-fat. She showed that the diet’s wisdom had been stated and received, never once proven to be right or right for all — the cholesterol studies, for example, were all done on middle-aged men, not on women — and dissenting voices were ignored.

Skepticism about low-fat grew and the tipping point came in the early 00s with the Atkins Diet fad. This high-protein, low-carb regimen caused followers to lose weight quickly and keep it off. Its own deficiencies emerged and by 2005 the Atkins company was bankrupt, but by then dieters had moved on and low-fat was done.

A Diet for Health

I’m not a nutritionist, but I’m not an economist either and I often write about economics – so I may as well give my thoughts. I’m not going to comment on popular diets like Keto or Paleo, because I don’t know enough about them. Also, as a diabetic on medications, including one in the GLP-1 family, what works for me won’t work for everyone.

With those caveats, let’s first stipulate that the consensus among nutritionists now is for a balanced diet, emphasizing fresh foods and avoiding excessive refined carbs and sugar. We know we don’t have to try to “get” our carbohydrates because they’re in much of what we eat, and there’s a risk that in “getting” them, people will eat food they think is healthy but isn’t. Many people probably count, as I used to, store granola and bran muffins as good choices, unaware that they’re ingesting more sugar than they can quickly metabolize unless they’re following breakfast with a mile run.

This point is key, as there’s growing scientific opinion that excess glucose causes inflammation that can lead not only to diabetes and cardiovascular disease but other diseases, possibly including cancer and Alzheimer's. Dr. Peter Attia, in the bestseller Outlive, while citing exercise as the main way to promote Healthspan®, also recommends restricting consumption of added sugar along with highly processed foods, refined carbs, and certain fats. Attia suggests a personalized diet based on carbohydrate tolerance, to be checked with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM).

As a CGM wearer,4 I have years of data about what kind of eating keeps glucose levels in the targeted “safe” range and what kind causes the artery-damaging spikes we want to avoid.

My glucose sensitivity is high in the morning, so almost anything carby I eat will cause a spike. No breakfast is worse for glucose control than simple carbs with added sugar, like most cold cereals. Informed diabetics don’t consume fruit salads or fruit juices unless combined with protein or fat. Eggs are fine, but I hate them. For me, a yogurt (2% fat) with fruit, unblended, keeps me in range all morning.5 Yogurt and other full-fat dairy, which got a bad rap in the 1977 Senate Report, may have health benefits that we are only starting to understand.6

My sensitivity at lunchtime isn’t as high, but sandwiches can cause a spike, unless the ratio of fat to bread is high. A cheeseburger is okay, though not healthy everyday fare — you can’t go crazy with the animal fat either — but turkey or tuna salad may not be. Fries are no good, except a few cadged from a friend’s plate. Obviously, salads containing some proteins are best.

In the late afternoon, my glucose tends to crash, and I start getting annoying beeps from my monitor. I eat an apple or nuts to get my sugar back up until dinnertime. My dinners usually combine meat and modest amounts of carbs and keep me in range. Certain carbs are riskier than others, especially rice (except Basmati, see note 9). A dinner of vegetables and jasmine rice, for example, will cause a vicious spike.

Desserts after dinner are fine, including cake or ice cream. Ice cream, in fact, I can eat any time and stay in range, presumably owing to its fat content.7 Similarly, neither wine nor (unsweetened) coffee seem to present any glucose problems, which I take as evidence of a benign God. Cake, however, will produce a different reaction depending on when it’s eaten — which leads into another issue.

Food Order

Jessie Inchauspé is a French biochemist who has with admirable self-confidence dubbed herself The Glucose Goddess. In her books8 and social media, she argues that the order in which food is eaten can help manage glucose. This makes sense: the stomach begins to digest the food that comes down the pipe first, and if it is something easily converted to glucose, like white bread, blood sugar will spike. If it’s fatty or complex, digestion will be slowed so that when the simple carbs appear, they’ll be at the back of the line.9

I’ve tested this and it works. I have a mild addiction to bagels10 and was sad when I heard from a nutritionist the words, “Diabetics don’t eat bagels.” If I start the day with a bagel, even scooped out and slathered with cream cheese, my glucose will spike. But if I prepare for a bagel fix by eating yogurt 40 minutes before, I can stay in range. Similarly, eating cheese ahead of a carby dinner usually works. When I have even a tremendous Georgian meal, which traditionally begins with khachapuri cheese-filled bread, my blood sugar usually goes down.

This is why cake on an empty stomach is bad, but after dinner tends to be okay.

Conclusion

Reading this over, I see that my criticism of food companies and the scientific consensus that can form around unproven theories makes me sound a little like RFK Jr. In fact, I agree with him when he calls out, say, the high fructose corn syrup lobby for keeping our food unhealthy — but those are areas where he probably won’t be able to change anything. It is in the areas where I think he’s wrong that he may be able to have an impact.

As for my nutrition advice in the second part of this post, as RFK Jr. would say, do your own research.

Jane Brody’s Nutrition Book (1982) and Jane Brody’s Good Food Book: Living the High-Carbohydrate Way (1985)

The history that follows is based on La Berge, “How the Ideology of Low Fat Conquered America,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences (2008)

The Guidelines effectively discredited high-protein programs like The Scarsdale Diet, which had been briefly popular in the 1970s after its creator was shot and killed by his ex-lover. (One comedienne said at the time, “I’d like to murder a diet doctor.”) Scarsdale presaged the Atkins Diet that became popular in the 00s but was more extreme, recommending “plenty of steak” on Sundays.

I use an Abbott Freestyle Libre 3 and am available to be a brand ambassador.

I prefer Fage since the fruit is in a separate section, so you can easily control how much you use. Again, available to endorse.

For more on the possible benefits of dairy, listen to the podcast linked in the latest Substack by The Skeptical Cardiologist. (Dannon had an old commercial featuring nonagenarians in the Caucasus who ate a lot of yogurt, and maybe they were onto something.)

According to one of the happiest magazine articles I’ve ever read, Harvard researchers found ice cream is good for cardiovascular health. Johns, “Nutrition Science’s Most Preposterous Result”, The Atlantic (May 2023). The researchers quashed their own study because its result was so counterintuitive as to endanger their reputations.

E.g., Inchauspé, Glucose Revolution (2022)

GLP-1 drugs do something similar for diabetics, slowing the digestive system. Basmati rice has a molecular structure that causes it to be digested more slowly than other kinds.

A great bakery called Kossar’s Bialys opened in my neighborhood, which was like a liquor store coming to an alcoholic’s corner. My wife spotted me coming out the other day and said, “I see you’re using again.”

Jane Brody's my friend and neighbor. I think this piece is a great job synthesizing your nutrition science experience and data, and, I believe, so would she.