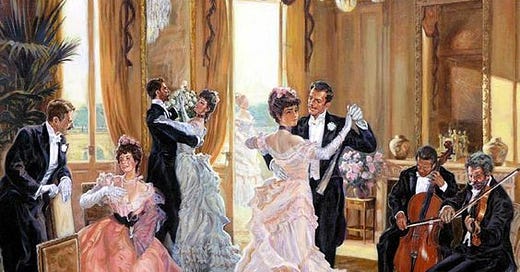

My analyst and I were discussing a Slovenian stock that we had considered buying for our portfolio and passed on, and which has skyrocketed. I said, “You can’t dance with all the pretty girls at the party.” This old traders’ expression means that there are always going to be great opportunities you miss, even while you may be capitalizing on others.

After repeating this truism, I realized it’s no longer acceptable. First, it’s looksist and to avoid offense, you’d have to omit “pretty.” Also, the saying evokes a creepy image of boys selecting from girls waiting in a harem-like fashion. How about we change it to, “You can’t dance with all the boys and girls at the party.” Wait, what about the non-binary? Okay: “You can’t dance with the people of all genders at the party.”

But that’s ableist, as there are many who can’t physically dance. Can we substitute a more inclusive activity, like “You can’t talk to all the people of all genders at the party”? What about those who have social anxiety and can’t tolerate parties? Why should they be left out? Let’s say: “You can’t communicate over Zoom or social media to all the people.”

Check your privilege: the unhoused may not have access to the Internet. Can we finally agree on this formulation: “You can’t hang out on a streetcorner and talk to all the people who pass by.” Or maybe you can.

Whatever way you can say it today, I rate it mostly true. All investors miss out on great chances and shouldn’t beat themselves up over them. I don’t agree, however, with Maharishi Buffett’s oft-used absolutist adage, “In investing there’s no called strikes.” (This is what he says in public, anyway; supposedly in private he does a lot of moaning about winners he missed, especially Walmart.) The closer an opportunity is to your area of expertise, and the more obviously amazing it is, the less excuse you have for not swinging at it.

The stock I mentioned above was within our Eastern Europe mandate, operates in pharma, a sector we like, and the valuation was good. We had a couple of reservations that kept us from buying it and couldn’t have known they’d work out fine, so I’ll let us off the hook this time. Still, as a called strike, this one was worse for us than not buying, say, Nvidia, which is well outside our mandate and expertise.

But if you had a U.S. tech fund and didn’t buy Nvidia — the company of the decade and right in your wheelhouse — you’re right to kick yourself.1 I’ll do it for you, if you can’t reach.

What Isn’t His’n

Another discussion my analyst and I had last week concerned a short squeeze underway in Coreweave (CRWV), a recently IPO’ed AI data center company. As everyone who follows me probably knows, short selling is when you borrow a stock and sell it, expecting to buy it back later at a lower price and pocket the difference. It always seemed to me that most shorts are good at the borrowing and selling parts of the trade but underestimate the challenge of buying back.

Which reminds me of a saying attributed to a 19th century financier named Daniel Drew: “He who sells what isn’t his’n/Must buy it back or go to prison.”

CRWV has a limited free float, with 80% of its shares held by insiders or institutions and not tradeable. AI skeptics’ desire to bet against the boom and this company’s nosebleed valuation left them short of almost 50 million shares, over 30% of the free float. This made them vulnerable to good news, which soon arrived when CRWV announced more long-term contracts on their data centers.

As the stock has doubled, the shorts’ paper losses have reportedly mounted to $1.6 billion. I myself would be going insane. If you own a stock and it moves against you, the problem keeps getting smaller and the worst case is zero; with a short the problem gets bigger, and the potential loss is unlimited. But these CRWV icemen aren’t giving up even as new shorts enter, driving the cost to borrow shares up to 150%. With a base of strong-handed investors, who anyway are locked up, from whom exactly do these shorts expect to buy back the millions of shares they need?

The short sellers may yet prevail, but I doubt it. Years ago, a wise older investor told me that if you ever want to go short, “Pick on the weakest kid in the playground.” For AI, that would be a second-tier developer with a large percentage free float, not CRWV, tight-floated and backed by Goldman Sachs, Fidelity — and Nvidia itself (!), with a 6.6% stake. (I must give a shout-out to Jim Cramer, who I posted about two weeks ago, here, for pounding the table on CRWV post-IPO when it traded around $30 vs. over $140 today.)

Maybe the short sellers would be less reckless if their punishment was debtors’ prison, as in Daniel Drew’s day, and not just winding down their hedge funds to “spend more time with [their] family.” (It’s amazing to me how quickly managers get tired of their families and launch new funds, with reset high-water marks, of course.)

As for the general practice of selling what isn’t your’n, I heard another piece of advice years ago from a seasoned investor. He said when you’re starting out in the business, you should study your personality and decide whether you’re a natural long (i.e., an optimist) or short (a skeptic). I’m an optimist and often foolishly so, but then again, as they say, you don’t meet a lot of rich pessimists.2

18 months ago, I attended a dinner in Silicon Valley with semiconductor experts, most of whom had never bought any Nvidia and were gnashing their teeth over it. Worse, all but one said it was now “too late” to buy it – and have since missed another 100% gain. Fortunately, I had to buy some when I heard them say that.

I’ll give the last word on shorting to the Maharishi, in a talk he gave at Columbia Business School in 1993, reprinted just today in

:Buffett: Going short is betting on [when] something will happen. If you go short for meaningful amounts, you can go broke. If something is selling for twice what it’s worth, what’s to stop it from selling for 10x what it’s worth? You’ll be right eventually — but you may be explaining it to somebody in the poorhouse. (Laughs)