Note: If you like this or any of my other posts, feel free to share.

In more than one prior post I mentioned that I enjoy the quarterly letters sent by several hedge fund managers. One is Howard Marks of Oak Tree, an asset management group mostly working in credit, also real estate and equities. I came across Marks’ latest “Memo,” as he calls it, which discusses the bubble-like nature of the U.S. stock market, particularly the Magnificent Seven. While he’s not predicting an imminent crash, he shows that, historically, investment performance has rarely been very good when the entry point was anywhere near current levels.

I find little to disagree with there,1 but it was another part of the Memo that caught my eye. Marks writes that early in his career he formulated some guiding principles that carried him along for the next 50 years. Screenshot is below.

While these principles all seem to make sense, unfortunately applying them in the stock market would’ve resulted in massive underperformance for the last ten years. To be fair, Marks acknowledges that he isn’t primarily an equity manager; maybe his principles still work well in credit. I don’t know, though Oak Tree’s ongoing success suggest that they do.2 So, why haven’t these principles been working for stocks?

My partner Steve Gorelik recently analyzed the historical performance of the U.S. equity strategy he manages, and what he found provides some insight. For at least the last decade, buying companies mainly because they were cheap more often than not led to losses. Thus, Marks’ principle that “there are few assets so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain” simply doesn’t work today. I will suggest later some reasons why, but first, here is an excerpt from Steve’s analysis.

In the [U.S. strategy’s] portfolio, investments are placed into one of the following categories:

· Cash Flow Growth at Reasonable Prices – Companies that are growing revenues and profits at an annual rate of 5% or more while trading at a price that we consider to be attractive for that level of growth

· Growth with Temporary Problems – Companies that have the potential to grow annual revenues and profits at a rate of 10% or more but, for one reason or another, are dealing with a temporary setback

· Value with a Moat – Companies operating in industries with natural growth rate of 5% or lower but allocating capital in a value-added manner and trading at a very attractive price

Usually, the portfolio is more or less equally split between these categories, but more than half of the investments that failed to beat the benchmark came from the Value with a Moat category.

Given these results, it is tempting to dismiss the whole Value with a Moat category as “uninvestable,” but that would be succumbing to recency bias given that value companies have usually outperformed the market over long periods but haven’t done so in the last five years. We had several successful investments in this category, including Owens Corning, FMC Technip, and Ameriprise Financial. The common theme amongst those “winners” is that they are high-quality, well-run companies gaining share in stable industries. The combination of these factors leads to expanding margins and, in turn, strong market performance. That said, there have also been a fair share of less successful outcomes.

We looked at the companies purchased since the inception of the strategy that fell into this segment and assigned them further attributes such as High Leverage, Declining Addressable Market, Declining Margins, etc. While each of these measures impacted performance, one characteristic, the declining addressable market, seems to be overwhelmingly to blame for many of our poor decisions over the years. The takeaway is: Don’t buy companies with shrinking addressable markets.

A solid counterargument can be made by people investing in high-quality companies with a shrinking consumer base, such as tobacco. Still, one should know what they are good at and where the decisions usually prove faulty. It turns out I am not a good “cigar butt” investor.

What Happened to Deep Value?

Firebird’s experience over the last ten years thus contradicts Marks’ second principle: “Good investing doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.” Making well-timed trades on bad companies or ones with dimming prospects is not a route to success in the current equity world. And contrary to Marks’ first principle, it is very much “what you buy” that makes the difference, not “what you pay.” Great companies in stable or growing markets have been where to be and, unless someone can convince me otherwise, they still are.

I have some ideas as to why buying cheap hasn’t worked in the stock market for so long, the first being the trend away from active management toward indexing. There are simply fewer investors around seeking out “bargains,” so you can be alone with your discovery for a long time. Attend any gathering of the dwindling number of true value investors3 and you will hear moaning about why no one is following them into the great stock they found:

“It’s the only manufacturer of cabooses for railroads in the Dakotas and it trades at half of book! Why is everyone sleeping on this?”

“They have been making shoelace tips for 100 years and have a 4 P/E!”

“There’s still a market for typewriter ribbons!”

Guys, the reason no one is following you into your deep value stocks is NO ONE CARES. In Marks’ debt world, it doesn’t matter if anyone else cares, as long as the company pays off at the end.

Besides the impact of stock indexing, the speed and magnitude of tech-enabled disruption has seen venerable companies lose their entire market in short periods of time. Investors will avoid companies in vulnerable sectors no matter how cheap they are and, as Steve found with an investment in U.S. regional telecoms, Marks’ “what you pay” doesn’t help.

Whither Value Investing?

The news for value-seeking investors is not all bad. Steve identified a slice of his strategy that, despite being fundamentals- and not momentum-driven, did well. See below.

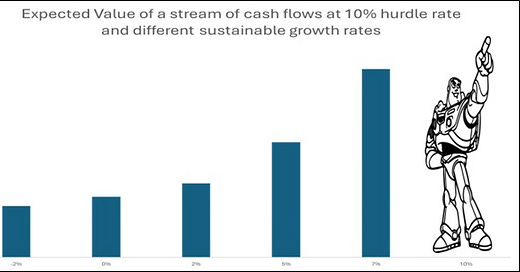

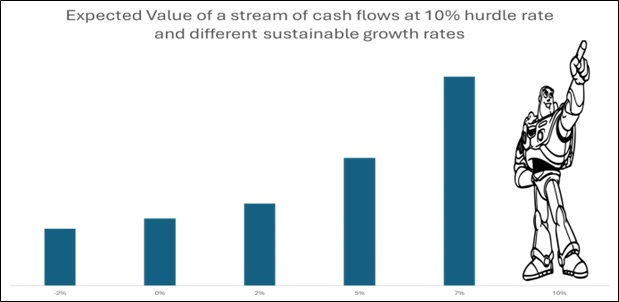

Nearly 1/3 of all investment decisions made [in the U.S. strategy during the ten-year period analyzed] resulted in IRRs of 30%+ with an average holding period of 600 days. By analyzing these 40 or so investments, accelerating growth was often noted as the reason for outstanding performance. To make it into this category, the company doesn’t need to be fast-growing; its growth just has to be higher than its most recent results in order to generate multiple expansion that usually accompanies these situations. The mathematical reason for the expanding multiple is in the Terminal Value, which grows exponentially with a higher assumed normalized growth rate.

Finding this type of opportunity is easier said than done, but we feel comfortable that we will be able to uncover enough of them over time. Currently, there are several companies with these attributes in the portfolio.

The takeaway is: Look for companies with an inflection point that will accelerate growth and expand margins.

Conclusion

All long-time investors have principles that guide their careers, but at some point the world moves on, and it’s necessary to move with it. Had Warren Buffett not moved, 20 years into his investment career, from cigar butts and old economy value to quality and growth, you would not today recognize the name Warren Buffett.

Maybe in a future post I’ll discuss the famous out-of-print book Margin of Safety by Seth Klarman ($1,999 on Amazon), and how its investing principles have become mostly obsolete for anyone managing outside, non-permanent capital.4

At least I didn’t until I watched the Goldman Sachs ISG client Zoom this morning (1/10/25), which made a decent argument to the contrary. Now I’m just confused.

Let me note that in terms of size, if Marks’ $200b AUM Oak Tree and mine were animals, his would be a large giraffe and mine a small rabbit. I learned this from Gemini AI and then, for fun, asked if a rabbit can critique a giraffe. Gemini’s answer is worth quoting in full:

In a literal, physical sense, no. A rabbit can't physically harm or overpower a giraffe. A rabbit's bite wouldn't even be felt by a giraffe through its thick hide. [I see Howard Marks occasionally at fundraising events and have never yet tried to bite him.]

However, if we're talking metaphorically or in a fictional context, then yes, a rabbit can "criticize" a giraffe in several ways:

· Verbal criticism (in a fictional setting): In a cartoon, fable, or story, a rabbit could certainly make fun of a giraffe's long neck, clumsy gait, or any other perceived flaw.

· Symbolic criticism: The rabbit could represent a smaller, weaker entity pointing out flaws in a larger, more powerful one. This could be a metaphor for social commentary, where the "rabbit" represents the common person criticizing a powerful institution or leader ("giraffe").

· Observational criticism: A rabbit might observe that a giraffe has trouble reaching low-growing food or hiding from predators, which could be seen as a form of "criticism" of the giraffe's adaptations.

The last such group I joined, at a pub in Marylebone, included seven young male fund managers. As we stood in the corner alone, I asked why no women were coming over, as I’d heard that pretty girls were attracted to men who buy stocks with deep fundamental value.

If Baupost, Klarman’s fund, and mine were animals, they’d be a polar bear and an arctic fox.