Last month I made my first-ever pilgrimage to the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting in Omaha. This was overdue, since it was the writings of Warren Buffett and his mentor Benjamin Graham that had inspired my career as an investor. In 1993, having read Graham’s The Intelligent Investor soon after being politely asked to move on from the law firm where I’d been an associate, I began to buy stocks using the simplified value strategy Graham had laid out.

This was pre-Internet, so I got information on stocks by going up to the Columbia Business Library to study the Value Line books, which helpfully included ratings: 1 for Strong Buy down to 5 for Sell.1 It was there that I ran into a college friend of my wife’s, who lured me to Tom’s Diner on 113th Street (the one in Seinfeld) and tempted me with stories about the incredible value in emerging markets. He was a persuasive guy, and so we launched a friends and family partnership to do frontier markets, which got us into Russia early, which turned into Firebird.2 But that’s a story for another day.

The Berkshire Meeting is dubbed “Woodstock for Capitalists”, but to me the feeling was more like a Taylor Swift concert. First, you entered a giant Exposition Hall, accessible only to those with shareholder badges. At the merch booths you could peruse products of Berkshire operating companies, e.g., Brooks sneakers (special Annual Meeting edition), Borsheim’s Furniture, private jets, and lavish RVs. There were even Buffett and Munger “squishmallow” dolls, which resell at a markup on eBay. Devotion to the leader was shown by buying merch and wearing it into the arena; I got a baseball cap and some See’s Candies.

By the time I entered, the arena was already near its 19,000 capacity and I had to find a seat in the nosebleeds. The last time I’d sat that high up was probably for Pink Floyd’s 1977 Animals tour, the one with the inflatable pig, and I was probably too stoned then to care. Buffett’s appearance sent an electric charge through the crowd, as I imagine Swift’s does, and from that point on he could’ve read the Omaha directory or recited from the Koran and everyone would’ve been happy. But in fact he answered questions for four hours – beating Taylor’s three, although Warren got to sit the whole time. Though he covered Berkshire’s current state in detail, he didn’t leave out the greatest hits from his Eras: “the market is manic depressive, so you have to take a long-term view” being his “Shake it Off”; “we like companies with moats” his “Anti-Hero”; and “we only buy businesses we understand” his “Cruel Summer”.3

More interesting to me than what Buffett said is what he didn’t say – or rather, how he sidestepped questions he didn’t want to answer, knowing that any comment could move the markets. For example, when asked about Berkshire’s sales of Apple in Q1 he cited only the desire to lock in capital gains before tax rates go up, saying nothing about the position’s huge weighting in his portfolio (which might’ve implied he’d still be selling more and hurt the stock) and nothing about how the company was still a good value (which could’ve looked manipulative if he did sell more). Other questions he preferred not to handle were evaded by answering the preceding question a second time. Maybe he thought attendees would assume that he’s just a 93-year-old grandpa and getting forgetful – but I think the opposite was true. This guy is sharp cheddar.

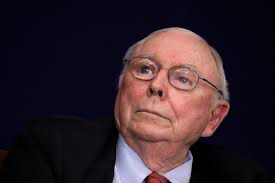

The moving part was a filmed tribute to Charlie Munger, Buffett’s long-time partner, who died earlier this year, just short of his 100th birthday.4 Buffett credited Munger as the architect of Berkshire’s strategy to buy into quality growth companies at reasonable prices, and humbly referred to himself as merely the carpenter who lays the floorboards. In further tribute to Munger, the only book for sale at the Expo bookstore was Poor Charlie’s Almanack, a collection of his writings and speeches. I bought a copy, devoured it, and had a few initial observations. I’m sure I’ll have more as I reflect on the book or reread it.

Behavioral Investing

Munger spoke and wrote about how investors’ psychology led them into mistakes, at a time when such an opinion was contrary to almost everything being taught in economics courses and business schools. By now, views like Charlie’s are well-accepted and organized by people like Nobel winners Kahneman and Tversky, James Montier, and others. Reading Munger’s speeches from the 1980s, you sense his frustration to the point of outrage at the dominance of so foolish a thing as the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), i.e., the idea that markets are perfectly efficient, incorporate all available information, and therefore it is impossible to outperform. If this is true, then “value investing” is not a thing.

When we started Firebird, one of my co-founders, the late (and greatly missed) Brom Keifetz, had just graduated from UCLA Business School and was steeped in EMH. I remember arguing the opposite position, as a believer in Ben Graham, and noting that in my prior job as an M&A lawyer I had seen plenty of irrational behavior. If people periodically went crazy in the private markets, why wouldn’t they also do so in the public ones?5 Brom agreed to join Firebird only because he could accept that Russia, in the midst of political and social turmoil, was capable of market inefficiency – such as the 1994 voucher program that appeared to value a large portion of the Russian economy, including world-class oil companies, at just $10 billion.

Always Invert

One of Munger’s mantras came from the German mathematician Carl Jacobi, who said, “man muss immer umkehren”, translated as “Invert, always invert”. Coming from algebra, inversion as a thinking tool means turning the problem around to see it from another side, e.g., instead of asking how to do something, ask how not to do it. In his army service, when Munger was asked to design flight paths for pilots, he approached the task by asking what kind of path would guarantee a crash and worked backwards from there.

In his book, Munger gives examples of problems approached by inversion, but I thought of one that illustrates the concept well. My former assistant interviewed for a job at the hedge fund D.E. Shaw, and one question on their test was to guess how many gas stations there were in the U.S. The question wasn’t to see her knowledge of the downstream oil industry, but how she would go about solving the problem. An initial approach might be to think how many cars there must be in the U.S., how many stations per state, etc. But a better way might be to ask how many cars per day a gas station would have to service to stay in business and work back from there. I don’t know what’s the best method – my own guess was way off, and I wouldn’t have gotten a job at D.E. Shaw. She did and is a champion real life problem-solver. Correct answer is in the footnote.6

In investing in emerging markets, Firebird often tries to divine the truth not from anything a company or brokerage analysts say – which frequently is misleading – but from what they don’t say, as well as other non-information that creates a mosaic. Just one example from hundreds I have: in the early days of the Ukrainian stock market an oleaginous broker came to New York pitching all the main exchange-listed stocks – except one, the one that to us seemed most interesting. He never mentioned the other one at all. Of course, it turned out that omitted stock was the only good one and the broker’s more important clients were already likely looking for shares, while the others were low-quality, with plenty of sellers. In reference to Sherlock Holmes’ Hound of the Baskervilles, I call that situation “The Dog that Didn’t Bark”.

Extrapolation Bias

Existing in the penumbra between recency bias (we overweight recent events), endowment effect (we overvalue things we own), and overconfidence, extrapolation bias refers to our tendency to assume past trends will continue. Munger, despite his focus on psychological investment mistakes, fell victim to extrapolation bias regarding Coca-Cola in a 1996 speech that is printed in the Almanack. Coke was then the star of Berkshire’s portfolio, its shares having risen 33x since 1982, and Munger seems to predict that it can continue to grow its value by 8% per annum, to reach a $2 trillion market cap by 2034. In reality, Coke’s stock struggled for years after that and today is worth just $275 billion, after underperforming the S&P Index by 500% since the day of the speech.

Firebird has experienced our share of extrapolation bias, including just recently enduring a 30% correction in a large position that had tripled over the last two years, leaving us starry-eyed and vulnerable. Although we’ve read the books and are aware that trends should not be extrapolated, when we do it there is always a “this time is different” explanation. If even a giant like Charlie could fall into a bias trap, how can we non-Charlies hope to avoid it?

Think about extrapolation bias the next time you look at the Nvidia chart. There is little doubt that artificial intelligence will transform businesses and our daily lives, but whether Nvidia can ever earn what the market is forecasting is the $3 trillion question, which I personally have no idea how to approach. I would suggest inverting it.

At this point I would normally (casually) note that I went to Columbia undergrad and find a way to also wedge in Harvard Law, but I’m ashamed of both schools now so I’m not going to even mention them.

It was a spring 1994 piece about Firebird in Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, called “Graham and Dodd in Siberia” or words to that effect, that really put us on the map.

As Taylor Swift became the largest cultural phenomenon that I’d had no part of, I felt obliged to give her oeuvre a listen. I even made a Spotify playlist of my favorites.

It was Munger’s death that inspired me to finally attend the meeting after talking about it for years. Any meeting with Buffett attending could be the last.

Ironically, as a former professional horse-race handicapper, Brom should’ve known that there is such a thing as superior information or emotional behavior that creates a monetizable edge.

Approximately 200,000.

What advice would your former assistant have for someone who is trying to get better at fermi problems/guestimmation? I am asking because I read Superforceasting last year, and I believe this is a very useful skill. Thank you so much for your fantastic writing (discovering your substack just made me order your book). :)